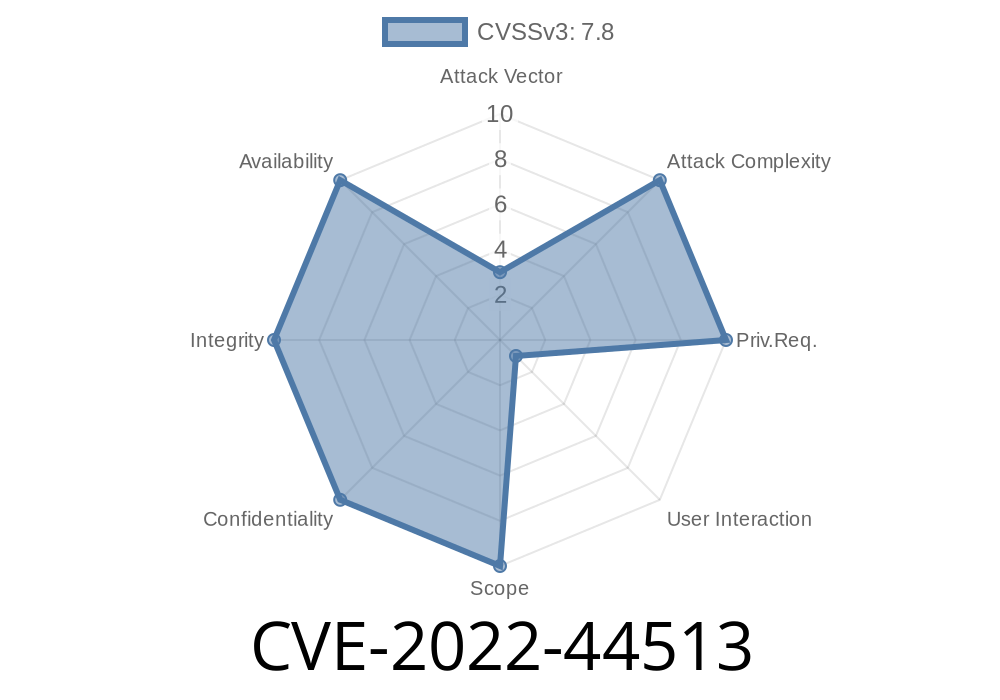

If you use Adobe Acrobat Reader DC to open PDF files, you may want to pay attention to CVE-2022-44513—an out-of-bounds write vulnerability that could lead to a full compromise of your system just by opening a single malicious PDF. This post breaks down how the vulnerability works, why it’s dangerous, and how attackers can actually exploit it—in language that’s easy to understand. Along the way, you'll find code snippets, real-world references, and actionable advice.

17.012.30205 (and earlier)

This bug allows out-of-bounds write—meaning that, when Acrobat Reader tries to process certain PDF data, it ends up writing memory outside the intended area. When software writes where it shouldn’t, attackers can feed it values that execute malicious code—such as malware or backdoors—using the rights of whoever opened the PDF.

What’s worse, it only requires you to open a malicious PDF. No fancy tricks, no extra downloads; just curiosity or carelessness.

Out-of-Bounds Write: The Basics

Before jumping into code and exploits, let’s explain “out-of-bounds write”.

Imagine a row of lockers (memory). Acrobat expects a PDF to have 5 items, so it gives itself 5 lockers. But a sneaky PDF says, “I have 20 items.” Acrobat trusts it and tries to fit 20 items into 5 lockers. The attacker can now stash their own items—some might be a weaponized payload—in neighboring, unprotected lockers. If the locker next door controlled the front-door lock (program flow), the attacker can basically open anything they want.

Technical Details

Adobe’s processing routines treat certain PDF objects or streams with insufficient size checks—meaning they don’t properly verify how much memory to allocate or access.

Although the exact vulnerable function is proprietary (Adobe doesn’t publish its source), researchers identified crash points when parsing complex object arrays or malformed image data.

For demonstration, let’s look at some pseudo-code representing the vulnerable logic

// Vulnerable pseudo-code

void process_array(uint8_t* data, uint32_t count) {

uint8_t buffer[10];

for (int i = ; i < count; i++) {

buffer[i] = data[i]; // No check if 'count' is > 10!

}

}

If count is, say, 20, this code writes past the buffer’s end—potentially overwriting important structures like return addresses.

In PDFs, this out-of-bounds access sometimes happens when parsing embedded images (/Image) or font streams with malformed /Length fields, tricking the program into “writing past the line”.

Attackers exploit this by creating a malicious PDF with specially crafted objects

1. Craft a malicious PDF (using tools like PoC PDF Generator).

2. Inside the PDF, set object fields (for example /Length or /Array size) to abnormally large values.

When Acrobat Reader parses this field, it allocates a buffer that’s too small.

4. Embedded exploit code in the field overflows out-of-bounds, overwriting control data that manages program execution.

Proof-of-concept snippet (metasploit-style, simplified)

pdf = PDF.new

payload = "\x90" * 100 + shellcode # NOP sled + reverse shell

pdf.add_object(

:type => 'stream',

:Length => 200, # claim too-large length

:Data => payload

)

pdf.save("malicious.pdf")

When a victim opens malicious.pdf in a vulnerable Acrobat Reader, the exploit runs immediately.

Videos & Research Links

- Adobe Security Bulletin: APSB22-56

- NIST NVD Record: CVE-2022-44513

Public PoC & Research Writeup:

- Paper on similar exploits

- PDF Explained: Exploit Development

Beware of unknown PDFs: Don’t open attachments from strangers.

- Sandboxing: Open PDFs in a restricted environment (like Chrome’s built-in PDF viewer or a virtual machine).

Closing Thoughts

CVE-2022-44513 is a classic reminder: even common, innocuous-seeming files like PDF can be weaponized with a bit of technical cleverness. Adobe’s quick patching means responsible users are safe—but attackers are always on the lookout for people who don’t update.

Keep your software fresh, your wits sharp, and treat every unsolicited attachment with caution.

*If you’re a security researcher or developer, always keep up to date with Adobe’s security bulletins, and stay curious!*

Timeline

Published on: 12/19/2024 00:15:05 UTC