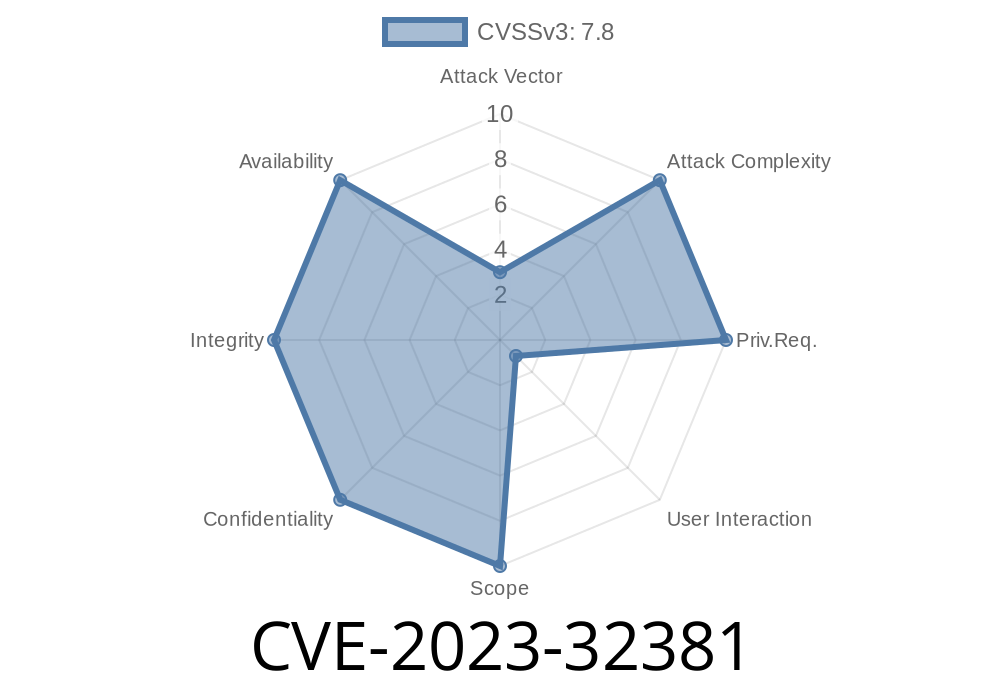

Apple devices are known for their privacy and security, but security holes sometimes still appear. One such critical vulnerability was tracked as CVE-2023-32381. This flaw, found in Apple kernel code, is a use-after-free bug that, if exploited, could let a malicious app gain full control over your device—with *kernel-level privileges*. In this post, we’ll break down what this exploit is, how it works, where it was fixed, and include references and example code to understand the issue better.

Apple Security Advisory Reference

- Apple Security Update for CVE-2023-32381 (Official)

- NVD CVE-2023-32381 Entry

What is a Use-After-Free (UAF) Bug?

A use-after-free bug happens when a program keeps a pointer to memory after it’s been freed (released). If an attacker manages to manipulate or access that freed memory, they can sometimes inject code or change core behavior, possibly leading to full system takeover.

In the Apple kernel context, such a bug is dangerous: the kernel has the highest access in the OS. By exploiting a UAF, a rogue app could escape sandboxing and do pretty much anything.

How Did the Vulnerability Happen?

The Apple advisory is very brief, but according to their release notes for CVE-2023-32381:

> “A use-after-free issue was addressed with improved memory management. An app may be able to execute arbitrary code with kernel privileges.”

This usually means that Apple code released a memory object, but something kept referencing it and, under the right conditions, an app could exploit that.

Here’s a typical pattern that can lead to a UAF

struct my_struct *obj = (struct my_struct *)malloc(sizeof(struct my_struct));

some_kernel_function(obj);

// Later

free(obj);

// ... but still using obj somewhere

do_something_with_obj(obj); // UAF: obj points to freed memory!

If there’s a bug in Apple’s IOKit or similar kernel frameworks, user-controlled input could drive these sequences.

Imagine a scenario like this in a kernel extension

void vulnerable_func(user_input) {

struct kernel_obj *obj = alloc_kernel_obj();

setup_obj(obj, user_input);

free_kernel_obj(obj);

// Oops! User input can trigger code that uses obj after free

if (user_input->trigger) {

process_obj(obj); // Access after free

}

}

Exploit code looks for ways to reclaim and control that freed memory before the use happens. At the kernel level, this might mean spraying the heap with controlled data.

Hypothetical Exploit Flow

While Apple hasn’t released exploit details, we can summarize a typical use-after-free exploit for Apple’s kernel:

1. Trigger the use-after-free: The rogue app sends crafted input to a kernel API (often via IOKit user clients).

2. Reallocate the freed memory: Fill the system heap with attacker data to occupy the recently freed memory.

3. Cause kernel to access the freed object: Make the kernel access the object again, but now pointers and function tables inside point to attacker's data.

4. Gain code execution: Redirect the kernel to execute rogue code, escalating privileges or installing a persistent backdoor.

Example Exploit Snippet (Demonstration Purposes)

Below is a NON-working illustrative code snippet showing heap spraying in userpace, used in some real-world kernel UAF exploits (adapted for teaching):

#define SPRAY_SIZE 10000

#define OBJ_SIZE x100

int main() {

void* spray[SPRAY_SIZE];

for(int i=;i<SPRAY_SIZE;i++) {

spray[i] = malloc(OBJ_SIZE);

memset(spray[i], 'A', OBJ_SIZE);

}

// Now, race trigger for kernel UAF bug (via IOConnectCallXXX, for example)

// The attacker hopes the kernel UAF-ed object is filled with 'A's

// This would break the system or run payload if function pointers are overwritten.

}

On a vulnerable kernel, this technique could help an attacker win a race for the freed slot.

Practical exploit details for Apple's kernel are *not* public as of June 2024, and responsibly so.

How Was CVE-2023-32381 Fixed?

Apple just says: “Improved memory management”.

Update! Patch your devices to the latest releases (iOS 16.6, macOS 12.6.8, etc.).

- Don’t run untrusted apps or sideload software, especially on older/macOS versions.

References & Further Reading

- Apple Security Update for CVE-2023-32381

- NVD CVE-2023-32381

- Introduction to Use-After-Free Vulnerabilities

- Project Zero - Kernel UAF Case Studies

Final Thoughts

CVE-2023-32381 is a shining example of why even the most robust systems need constant vigilance. Apple caught this serious kernel bug before public remote exploitation, but similar vulnerabilities do recur. The best defense is keeping your devices up to date and only running trusted code.

If you’re interested in digging deeper, browse Apple’s release notes and watch for security research write-ups once embargoes lift.

Timeline

Published on: 07/27/2023 00:15:14 UTC

Last modified on: 08/02/2023 00:42:34 UTC